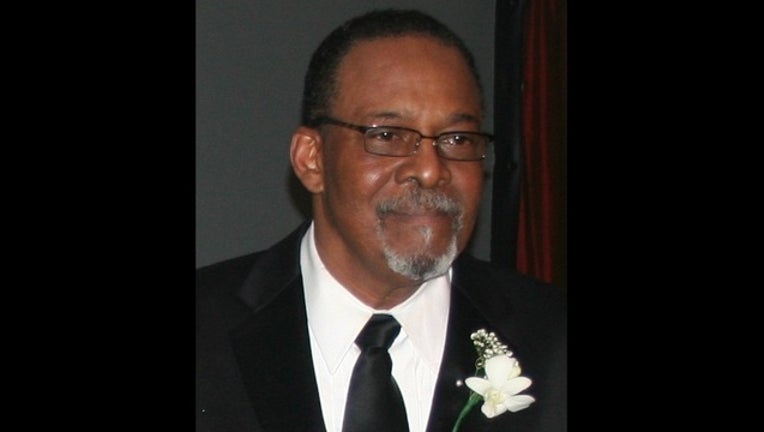

Henry English, who ran Black United Fund, dead after crash at 73

CHICAGO (Sun-Times Media Wire) - Even in his 70s, Henry English was perpetually on his way to one event or other. A protest. An organizing meeting. A lobbying trip to Springfield to speak on behalf of the needy.

Mr. English was a dervish-like presence in Chicago’s struggling neighborhoods for more than 40 years, a Black Panther leader who in the 1960s recruited a young Bobby Rush, an organizer for Mayor Harold Washington and the founder of the charitable Black United Fund of Illinois.

On Saturday morning, Mr. English was driving on Lake Shore Drive to a get-out-the-vote event for Democratic presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton when his van was rear-ended near 63rd Street, his longtime friend Conrad Worrill said. Mr. English apparently suffered a heart attack and died at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, the Chicago Sun-Times is reporting. He was 73. An autopsy Sunday was pending and did not rule on his cause and manner of death.

The other driver was unhurt, though his car was totaled.

“He was always running,” said Mr. English’s son, Nkrumah English. “When he was passing away, he was running somewhere. He had family life, work or a meeting every waking moment — the stamina he had to run all across the city, the state.”

Mr. English grew up on the city’s Near West Side, blocks from Farragut Career Academy. He was the second of four children raised by parents who came to Chicago from Mississippi.

After a post-high school stint in the Marine Corps, he returned to Chicago and became an activist while studying and serving in student government at what was then called Crane Junior College, where he rallied classmates to the cause of changing the school’s name to Malcolm X College, according to Worrill, who is director of the Jacob Carruthers Center for Inner City Studies at Northeastern Illinois University.

Mr. English eventually became the treasurer of the Black Panther Party and, in a turbulent era, emerged as a calming presence with a “genius” for community organizing, Worrill said.

“He had a peaceful, calm demeanor,” Worrill said. “He loved Malcolm, but he wasn’t stuck like that. He had a great appreciation for Dr. Martin Luther King.”

Mr. English moved his family to New York, where he studied at Cornell University and earned a master’s degree, then returned to Chicago and took a good-paying job as a health-care administrator. But he spent evenings organizing neighbors to fight for one cause or another, his son said.

Mr. English had key, behind-the-scenes roles in efforts that included voter-registration initiatives that helped propel Washington’s election as mayor in 1983. He also worked to preserve the buildings at the South Shore Country Club and transform them into the South Shore Cultural Center.

“When I was a kid, I used to hate to go out to the store with him,” his son said. “We’d go some place, and he’d have an hour long conversation with someone, and I’d have to sit there. Everybody knew him.”

His career as a health executive turned out to be short-lived. In 1983, Mr. English founded the Black United Fund in Chicago, which raises charitable donations to provide grants and expertise to small not-for-profit groups and programs for job-training, his son said.

Though Mr. English counted figures such as Fred Hampton and Stokely Carmichael as friends and rubbed elbows with jazz greats Count Basie and Miles Davis while doing organizing, he was proudest of his work helping working-class families in his hometown, according to his son.

“To him, the first step was economic development and getting folks back to work,” his son said. “He could have moved anywhere after he got out of Cornell. He could have made money in the corporate world. He came back to be in the fight.”

Mr. English is also survived by his wife, Denise; another son, Jummane; and daughters Kenya and Kamillah. Funeral arrangements are pending.